I’ve always been intrigued by a fleeting mention in Ellen Willmott’s previous biography: an invitation to lay out a garden for the Emperor of Japan. She turned it down, we’re told, because she had ‘too much to do in Europe’.

Author Audrey le Lièvre admits there is no date and no evidence for the story but feels it bears ‘the ring of truth’ and takes Ellen’s refusal as a sign of just how little she cared for money as ‘she could certainly have done with a replenishment of her resources’.

Ellen around the time she would have known the Japanese Ambassador. Image: (c) Berkeley Family and the Spetchley Gardens Trust

I am inclined to agree with Audrey’s first thought but not the second. The story does sound possible. Japan was still (just about) in its Meiji modernization period, still (just about) keen to take on Western ideas, and Willmott was at her influential peak. But I am also pretty sure that, for an Edwardian lady ‘amateur’, this would not have been a paid gig. It would have been considered an honour to create a garden for the Emperor, not a money-making wheeze. My gut is that Ellen simply couldn’t afford the fare. Appearing ‘rude’ was preferable to admitting she was, at the most likely point for the mystery invitation, almost broke.

But hold on… which garden are we talking about? It’s taken a long time to track down the puzzle pieces but this morning I made a bit of a breakthrough…

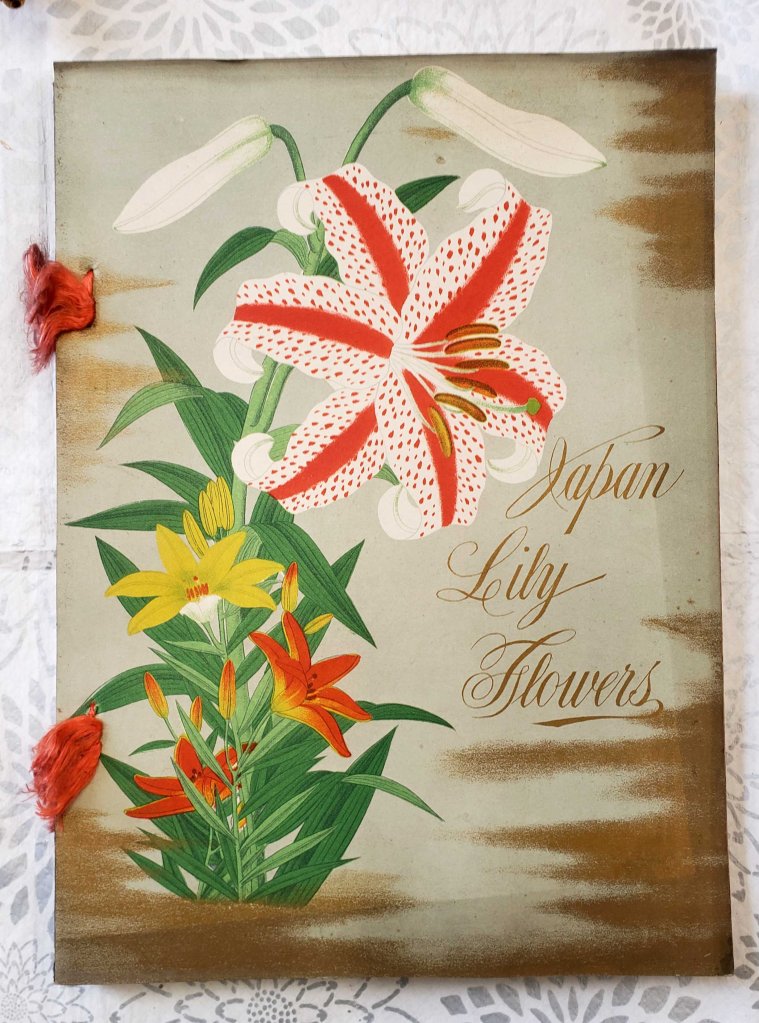

Ellen had been interested in the flora of Japan for many, many years. She followed the progress of plant hunters like Ernest Wilson, often contributing to their expeditions and enthusiastically growing the fruits of their labours.

She was also a customer of the Yokohama Nursery Co, purveyors of possibly the most beautiful plant catalogues the world has known. Here’s the cover of Ellen’s Yokohama Nurseries catalogue, 1894. The ‘brown’ bits are not staining, by the way, they are brushed-gold.

Image: Sandra Lawrence, courtesy of the Berkeley Family and the Spetchley Gardens Trust

In 1910, the Japan-British Exhibition, held at White City in west London, astounded eight and a half million gaping visitors over six heady months of wisteria-fuelled glamour. Paula Sewell has written a great blog about the event here.

The bucolic image of ‘Japanese life’ was not without its (mainly Japanese) detractors – but British people couldn’t get enough of the exotic gardens ‘recreated’ at the show. Here’s an image from my J-B Exhibition postcard collection:

And, just for kicks, here’s another one that’s nothing to do with this post but amuses me. It is the death-defying Wiggle-Woggle ride, installed for visitors that prized larking around over looking at plants (I understand they exist…)

Ellen didn’t have anything to do with organizing the event but she visited, probably multiple times. We don’t know if she attended the opening shindig but it was almost certainly at some official do to do with the show that she was introduced to Fukuba Hayato, the modernizer of Japanese gardening.

The adopted son of a samurai poet and philosopher-turned Meiji official, Fukuba (1856-1921) studied western-style agrimony and landscaping in Germany and France. He learned the principles of viticulture and brewing, and introduced western grapes to Japan (indigenous vines had never been suitable for winemaking, hence the popularity of saki).

Fukuba also bred a Japanese strain of the French ‘General Chanzy’ strawberry and, rather sweetly, when not looking after the Emperor’s gardens, grew melons, canned sardines and made jam. By the time of the 1910 Exhibition, the ‘Vicomte Foukouba’ (sic) was an ambassador for the ageing Japanese Emperor.

On secondment in London, the Vicomte would have probably bonded with Miss Willmott over their mutual love of chrysanthemums.

In his sunset years the emperor had got heavily into horticulture and ordered a fabulous iris garden in the Imperial Palace for the Empress. At one point I wondered if this was the garden Ellen was invited to make – after all, she was famous for her irises. From this image, they are still there today.

But no, it’s just a little too early – the Emperor’s iris garden at Shinjyuku Gyoen was designed by Fukuba around 1910 – just before Ellen met him.

The pair clearly got on extremely well, though. The Vicomte visited Warley and, on his return to the Imperial Palace, he and Ellen wrote to each other, in a common language – French – agreeing a plant-swapping programme. Annoyingly we have not (yet) found much in the way of lists of what was exchanged, but the few letters we have are warm and collegiate (if rather formal) and continue for several years.

The old Emperor died in 1912. According to tradition, he was buried at Kyoto, but it was important to the Japanese people that he should be remembered in the modern capital, too. Today, the Meiji Shrine is one of Tokyo’s biggest tourist attractions, not least for the gigantic Chinju no mori ‘sacred forest’ that surrounds it. At the beginning, however, the landscaping choice was anything but fixed and Fukuba Hyato was one of the principle officials deciding what was to go around the memorial.

If the story about Ellen’s invitation is true (and let’s remember it IS just a story) I’m betting on the vicomte’s asking her to help landscape the Meiji Shrine.

Admittedly, my timing comes from a single mention in a letter, dated 1st February, 1914, where Ellen’s on-off friend Lady Mount Stephen congratulated her on her forthcoming ‘world trip’.

Ellen could have made a fabulous itinerary that year – in a coals-to-Newcastle-moment, she was already booked to judge a tulip festival in Holland, but she would have plenty of time to nip back to enjoy the second-ever Chelsea Flower Show, get over to St Petersburg in time to use her invitation to the bicentenary gala at the Imperial Botanic Garden on June 24th before, perhaps, visiting friends and growers both sides of America and relatives in New Zealand. Japan would have made a great stop-off after that and the timing is spot-on as far as plans for the Meiji gardens are concerned.

The Japanese government had established a steering committee in 1913. By early 1914 they had selected the site, hived-off an area for the shrine itself and begun to think about the garden. Fukuba Hyato had form inviting westerners to design for him – in 1902 at the Paris World Fair, he had invited Henri Martine to create a French garden at Shinjyuku Gyoen.

Even so I find it a little far-fetched to imagine he’d have invited a foreigner to design something so nationally significant as an emperor’s shrine. I can see him asking Ellen for advice and suggestions, though, which, perhaps, ‘Japanese whispers’ down the century have turned into a full-blown garden design.

Just for a moment, though, let’s play the speculation-game…What if it was a full garden the Vicomte asked Ellen to design?

Firstly it would have been a William-Robinson-style wild garden – there’s no doubt about that – though hopefully Ellen would have added a Japanese flavour too; the style was popular enough in the UK after that exhibition. She would have loved the century-old iris garden at Horikiri, which had plenty of carefully-curated wildness:

Fashions still leant towards the west (though were moving towards a more nationalistic view), and it’s possible a western-style, wild-planted park might have emerged in the centre of Tokyo, had Ellen visited.

But she didn’t. Nothing came of Ellen’s ‘world trip’. Just two days after Lady Mount Stephens’s letter the final demands began rolling in again, this time in earnest. Four months later Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, and nothing was ever the same again.

Fukuba Hayato and Hara Hiroshi, a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University, appointed a team of Japanese experts who blended the rapidly-dating western fashions with newly re-trendy traditional Japanese garden styling to create the fabulous, shady forest that dominates the capital today. And frankly, it’s the better for it.

I live in hope that more letters may surface from Fukuba Hyato, aka Victomte Foukouba, that might clear up this mystery. For now, however, it’s just possible (if improbable) to argue that Ellen Willmott’s poverty may have resulted in a forest in the middle of Tokyo. A butterfly flaps its wings…

My book Miss Willmott’s Ghosts: The extraordinary life and gardens of a forgotten genius is now available in ‘all good bookshops’.